Defining User Centric Designs

Accessibility, Inclusivity and Universality are the most commonly used terms for User Centered Designs (UCDs).

Terminologies

Accessibility: a facility that caters to users with varied abilities and removing barriers that prevent or limit usability.

Universality: the word Universal means ‘to all’, in case of design, Universality is a solution that caters to the largest range of users.

On the other hand;

Inclusivity: refers to the physical and social aspects of design where a variety of people are comfortable.

Importance of UCD’s

User Centric Designs are crucial in many aspects which can be classified as:

1.Physical factors: Ramps, Elevators, Signages, Tactile tiles, Heights of fixtures, Handrails, marked level differences etc. all count as physical features of barrier free design.

These provisions allow the use of space easily, comfortably and with little fatigue and ensure safety, making them highly desirable for transfer of people facing mobility setbacks ranging from temporary injuries to bedridden people.

2.Social factors: culturally relevant elements, graphics, flexible layouts that encourage group setup, communal open spaces all count as social aspects of inclusivity.

They aid in enhancing communication and increase productivity at the same time, fostering a sense of community among users. This can be seen in private and public environments.

3.Mental factors: Use of colors, light, acoustic and thermal insulation all contribute to a healthy mental state of being for a person.

They induce comfort, evoke a positive attitude, reduce distress and enhance attention along with a sense of belonging.

4.Laws & Ethics

Ideally, a ‘designed’ establishment is considerate, flexible, expandable and future ready in itself. Reality, however is different and to bring these model expectations to life society creates rules and regulations to be implemented which ensure a positive living and working environment.

These laws prevent injuries, accidents and disasters along with saving architects from severe lawsuits for not not adhering to norms.

Historical Context

Evolution of accessible design in architecture

The inception

Architecture prior to the 20th century used accessibility wantingly. While the existence of ramps incorporated as part of the infrastructure were a part of large scale structures, they in comparison to today are only foundational, whether that was intentional, in context to those days or an oversight, cannot be said for sure.

The age of industrialization

The period of industrial revolution saw an increase in accidental and war injuries leading to an evident need for accessibility, especially in medical facilities.

The emergence

After a series of disability rights movements in the 60s and 70s the U.S. launched its first accessible building standard in 1961. Followed by the US Rehabilitation Act and ADA,1990, and several others globally.

As a result architects and designers since the early 2000s began incorporating inclusive, flexible and intuitive features as part of their design process.

Principles of Accessible Design in Architecture

There are seven key principles of User Centric Design. I remember it as the FL-STEPS checklist,which stands for;

Flexibility: Instead of a rigid pathway, an adaptable plan of usage which accommodates the widest possible range of the user group.

Low Physical Effort: The travel distance, time and ease of usage which causes the user the least amount of fatigue possible.

Simple Design: Clear directional cues and flow of movement comprehensible irrespective of age, language or education.

Tolerance for Error: The space planning should be such that it survives unintended hazards and accidents caused during usage.

Equitable: The primary goal must be the equitable dispersion of resources to all user groups.

Perceptible: Information, may it be in the form of signboard or announcements must be clear and concise.

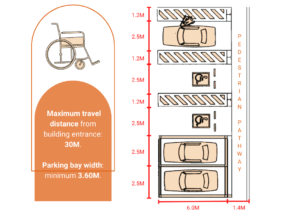

Sizeable: Provision of spacious areas, especially which expect a large congregation for traffic, maneuvering and transfer.

Common Barriers in Architectural Design

Broadly, barriers in architectural design fall under 4 categories:

Physical barriers: Level differences,steps, staircases, inappropriate heights of bathroom fixtures, cramped spaces,narrow doorways.These barriers prove impractical for persons with mobility impairment such as loss of limbs, injury, pregnant women, caregivers with strollers, elderly people, visually impaired people or people suffering from Cognitive disabilities such as obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) or even for people with hearing impairment because of lacking or unclear visual indicators.

Sensory barriers: Audio-visual cues such as tactile tiles, signages, smells of foods to body odors or even loud noises and poor or flooded lights are an assault to the senses of visually or audibly challenged or those with extreme sensitivities.

Cognitive barriers: Complicated planning, ambiguous directions, overtly stimulated environments and usage of non universal languages often act as cognitive barriers especially for those with sensitive mental health, such as autistic personalities, ADHD, even asthma or dyslexia.

Technological limitations: With the aging of the population, while there has been a surprisingly wide scale acceptance of some technologies from mobile phones to QR codes, many new technologies are still accepted with a grain of salt and are often viewed as alien entities. Not to mention a large portion of the population that belongs to the working class and have a flighty relation to formal school education, who also find themselves outcasts when it comes to use of devices beyond mobile phones.

Strategies for Accessible Design

With the principles of accessible design we understood the broad generalization of key areas which shall be remembered, here are some tailored strategies to follow with respect to space use-

Entrances and Exits: Distinctly marked and spacious doors, ideally motion sensored, with clear and wide pathways, Ramps and smooth transitioning spaces.

Interior Spaces: Clearance and maneuvering space, non slippery surfaces,smoothly transitioning, anthropometrically and ergonomically apt with adequate use of light and colors.

Signage and Wayfinding: Use of readable, clear fonts in high contrast placed strategically for maximum readability,use of braille and tactile at all key areas of movement, use of pictographs to eliminate or minimize language barriers and increase visibility, along with color coded zones, maps at regular intervals with ‘You Are Here’ indicators and arrows along with integration with technology such as touch less digital signages, QR codes, and even indoor GPS.

Lighting and Acoustics: Minimizing shadows and sudden lights, fixtures with consistent brightness, use of task oriented focus lights wherever necessary, easily operable controls, use of warm lights in personal and relaxation all areas and cool lights in work and public areas, use of smart technology for seamless and sustainable functioning.

Moreover, use of sound absorption material, insulation, vibration and visual alert systems and hearing assistive technologies help in developing an accessible environment for people with auditory and vision disabilities.

Outdoor Spaces:

All the above mentioned pointers apply for outdoor spaces, additionally, incorporating seating, shades, shelters, inclusive play equipment for children with special needs, careful landscaping, use of natural elements, accessible parking and secure evacuation routes and safe zones as part of the site.

Case Studies and Real-World Examples

Designed as a hub for organizations advocating for disability the Ed Roberts Campus is an exemplary model for a building with Universal design.

Features

- A prominent circular ramp as a central architectural feature.

- Fully accessible public transit connection through an underground BART station.

- Wide doors, adjustable-height workstations, and tactile paths for visually impaired users.

- Green features, such as solar panels, combined accessibility with sustainability.

Lessons

- Stakeholder Involvement: Collaborative design with direct input from disability advocacy groups ensured that every aspect of the design met user needs.

- Functionality Meets Aesthetics: Integrating functional accessibility with striking design proved universal design can be visually appealing.

The iconic Sydney Opera House, built in the 1970s, was not originally designed with accessibility in mind. Retrofitting began in the early 2000s to make the building universally accessible.

Features

Features- Installation of elevators, ramps, and automated doors.

- Hearing loops for performances to support individuals with hearing impairments.

- Tactile signage for visually impaired visitors.

Lessons

- Retrofitting Complexity: The original design posed challenges for implementing accessibility without compromising architectural integrity.

- Need for Forward-Thinking Design: This project highlighted the importance of incorporating accessibility at the planning stage to avoid costly retrofits later.

The Delhi Metro was one of the first major public transit systems in India to integrate accessibility into its design from inception.

Features

- Elevators, escalators, ramps, and wide entry gates for wheelchair users.

- Tactile tiles and announcements for visually impaired and hearing-impaired commuters.

- Special seating in trains and accessible ticket counters.

Lessons

- Standardization: Integrating accessibility from the beginning reduced costs and ensured consistent quality across all stations.

- Public Awareness: Educating the public on the importance of respecting accessible infrastructure, such as priority seating, remains an ongoing challenge.

A large-scale urban renewal project designed to improve public access to the Sabarmati River while prioritizing inclusivity.

Features

- Ramps, tactile pathways, and wheelchair-friendly promenades.

- Accessible toilets and shaded rest areas.

- Clear signage and easy navigation for people with mobility and sensory challenges.

Lessons

- Universal Design in Public Spaces: Ensuring continuous accessible pathways increases usability for all citizens.

- Integration with Public Transport: Accessibility improved the success of the entire project by connecting it to nearby transit networks.

A UNESCO World Heritage Site and a critical transit hub in Mumbai, CSMT underwent accessibility upgrades as part of a modernization project.

Features

- Ramps, tactile paving, and accessible restrooms.

- Dedicated seating and waiting areas for senior citizens and people with disabilities.

- Improved signage and auditory announcements for seamless navigation.

Lessons

- Heritage Constraints: Maintaining the integrity of a historical structure while introducing modern features posed significant design challenges.

- Phased Implementation: Upgrades had to be implemented in phases to avoid disrupting daily commuter traffic.

- Importance of Awareness Campaigns: Accessibility improvements must be complemented with education to ensure usage and respect by the general public.

Tools and Resources Design standards and guidelines

INDIA

- The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act (RPWD), 2016

- Harmonized Guidelines and Standards for Universal Accessibility in India

- National Building Code Of India

- Sugamya Bharat Abhiyan (Accessible India Campaign)

GLOBAL

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities ( UNCRPD)

- Americans with Disabilities Act(ADA), U.S.

- European Accessibility Act (EAA)

- ISO 21542: Accessibility and Usability of the Built Environment

Tools for accessibility assessment

- SAMARTHYAM ( A checklist developed by CPWD and NGO’ s for accessibility assessment

- GAATES Accessibility Certification

- Azure RP and Sketch

- ADA Compliance Checklist

- Wheelmap

Training and certification programs for architects

INDIA

- Accessible India Campaign

- NIEPMD (National Institute for the Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities)

- Samarthayam

GLOBAL

- International Association of Accessibility Professionals (IAAP)

- Rick Hansen Foundation Accessibility Certification (RHFAC)

- Design for All Foundation (Europe)

- World Bank Inclusive Design Training

Resources for accessibility

- Inclusive Design Toolkit (University of Cambridge)

- Tactile Signage Libraries (India)

- Accessible India Mobile App

- Web Accessibility Initiative (W3C-WAI)

- Global Universal Design Commission (GUDC)

The Future of Accessible Design in Architecture

Emerging technologies

Smart Assistive Systems

Use of AI, Robotics and IoT in spaces for easy and inclusive navigation.

Virtual and Augmented Reality (VR/ AR)

First hand experience of building through VR and on spot guidance through AR is possible today.

Adaptive Interior Spaces

Responsive and dynamic facades with modular spaces that may be transformed as per requirements.

Advanced Materials

Sensory Friendly Materials

Low allergy potential materials with tactile cues and acoustic insulation.

Lightweight and Flexible Materials

Availability of customizable materials using 3D printing technology, self recovering materials that return to original shapes during specific temperatures.

Renewal and Recyclable Materials

Degradable natural materials that can be recycled hence reducing overall environmental impact.

Trends towards Inclusivity and sustainability

Universal Design Principles

Holistic planning and community participation go a long way when it comes to designing people.

Green and Inclusive Spaces

The resultant product shall be both physically as well as monetarily accessible using therapeutic landscaping and net zero, cost effective spaces.

Policy and Standards Evolution

Emerging codes for accessibility enforce the global inclusive and sustainability design process

Inclusive Transit and Urban Spaces

Integration of universal design with local public transportation systems.

Conclusion

With time we are demographically shifting towards an aging population which promotes user centric design from being a necessity to an integral part of building design to enhance user experience, increase market value and prepare future ready, safe and inclusive infrastructures which are ethically and legally compliant.

And it’s a wrap!

It’s official. I have a writing addiction!

There’s just so much to share on this topic. I hope this deep dive was valuable for you.

What stood out to you the most? Were there aspects you think deserve more focus or anything I missed? Let’s keep this conversation going—your insights are just as important as the ideas shared here.

Feel free to connect with me on Instagram or LinkedIn. Share your thoughts—was this helpful? Did it spark any new ideas or perspectives? I’d love to hear how you approach these challenges in your own work.

And hey, if you’ve spotted other ways to bridge the gaps in accessibility, inclusivity, and universality, let’s discuss them! Together, we can push boundaries and set new standards in design.

P.S. What topic should I tackle next? Drop your suggestions in the comments or send me a message. Don’t forget to like, share, and comment—it means the world to me!

References

- Access Action Plan. (NA, NA NA). Sydney Opera House. Retrieved November 17, 2024, from https://www.sydneyoperahouse.com/about-us/how-we-work/strategies-and-action-plans/access-action-plan

- Accessibility. (na, na na). Sydney Opera House. Retrieved November 17, 2024, from https://www.sydneyoperahouse.com/visit/accessibility

- Delhi Metro: A UX Case Study. Every day, countless people rely on the… | by Shaily. (2024, March 1). Medium. Retrieved November 17, 2024, from https://medium.com/@lakhani.shaily/delhi-metro-a-ux-case-study-020dfb1b101f

- Ed Roberts Campus. (na, na na). Center for Architecture. Retrieved November 17, 2024, from https://www.centerforarchitecture.org/digital-exhibitions/article/reset-towards-a-new-commons/ed-roberts-campus/

- Rahman, F., & sharma, d. (2019, July 31). Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project | PPT. SlideShare. Retrieved November 17, 2024, from https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/sabarmati-riverfront-development-project-159693518/159693518

- Sydney Opera House Decade of Renewal – Accessibility and Safety. (NA, NA NA). Arup. Retrieved November 17, 2024, from https://www.arup.com/projects/sydney-opera-house-decade-of-renewal-accessibility-and-safety/

- Sydney Opera House emerges with a whole new sound thanks to an acoustic refit. (na, na na). The Spaces. Retrieved November 17, 2024, from https://thespaces.com/sydney-opera-house-emerges-with-a-whole-new-sound-thanks-to-an-acoustic-refit/